English is not my native language. I write, or at least try to write in it because I’ve been living in anglo countries for many years, and because it has become a sort of universal language these days. But I never seem to master it completely, its mysterious core somehow always evades me; and I think the reason is that its logic and cadence are so different from what seems more natural to me.

I grew up speaking Spanish and Portuguese. Later I learned Italian and French (although my French could still improve). Latin or romance languages feel more musical, more normal. I like to read in Italian especially, perhaps it would be my favourite language, with French second.

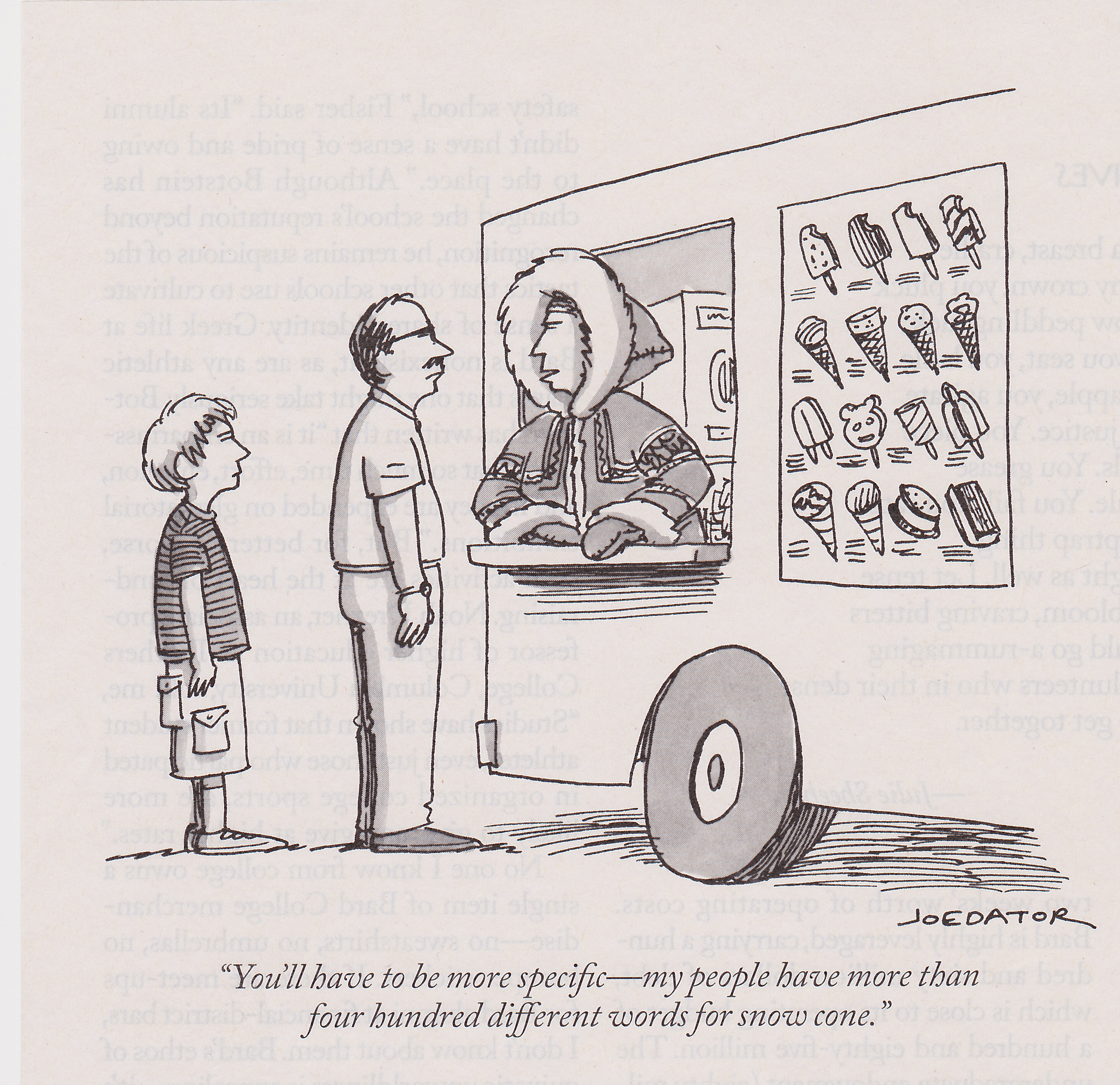

English has some advantages. One of them is the extremely large vocabulary, shorter words and a relatively easy grammar (compared to, say, German or slavic languages). But other aspects of it, such as spelling and pronunciation, make much less sense. But I think the main difference is in the little things. Like the lack of diminutives: in Spanish you would say “casita”, in Italian “casetta”, in English you’d have to say “little house”. It’s just not the same thing.

Of course it has other advantages and its own kind of beauty and a certain flexibility that you won’t find in romance languages. I think the real problem, for me, is

There is a theory that language, and in particular the language of our childhood, determine or at least shape our thoughts. There is a certain truth to it, as ideas come also from the means to express them, or, rather, they are interdependent: you need words to express ideas, and you need concepts or ideas to form words. According to what is called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, our experience of the world is based on the structure of the language we habitually use. According to Whorf, the formulation of ideas and thoughts is not a rational independent process but is determined by the particular grammar and vocabulary of the language in which these ideas are expressed. The world is organized and made sense of through language.

I don’t know; maybe there’s something to it, n’est ce pas? ¿No lo crees? E se non è vero, è bene trovato.